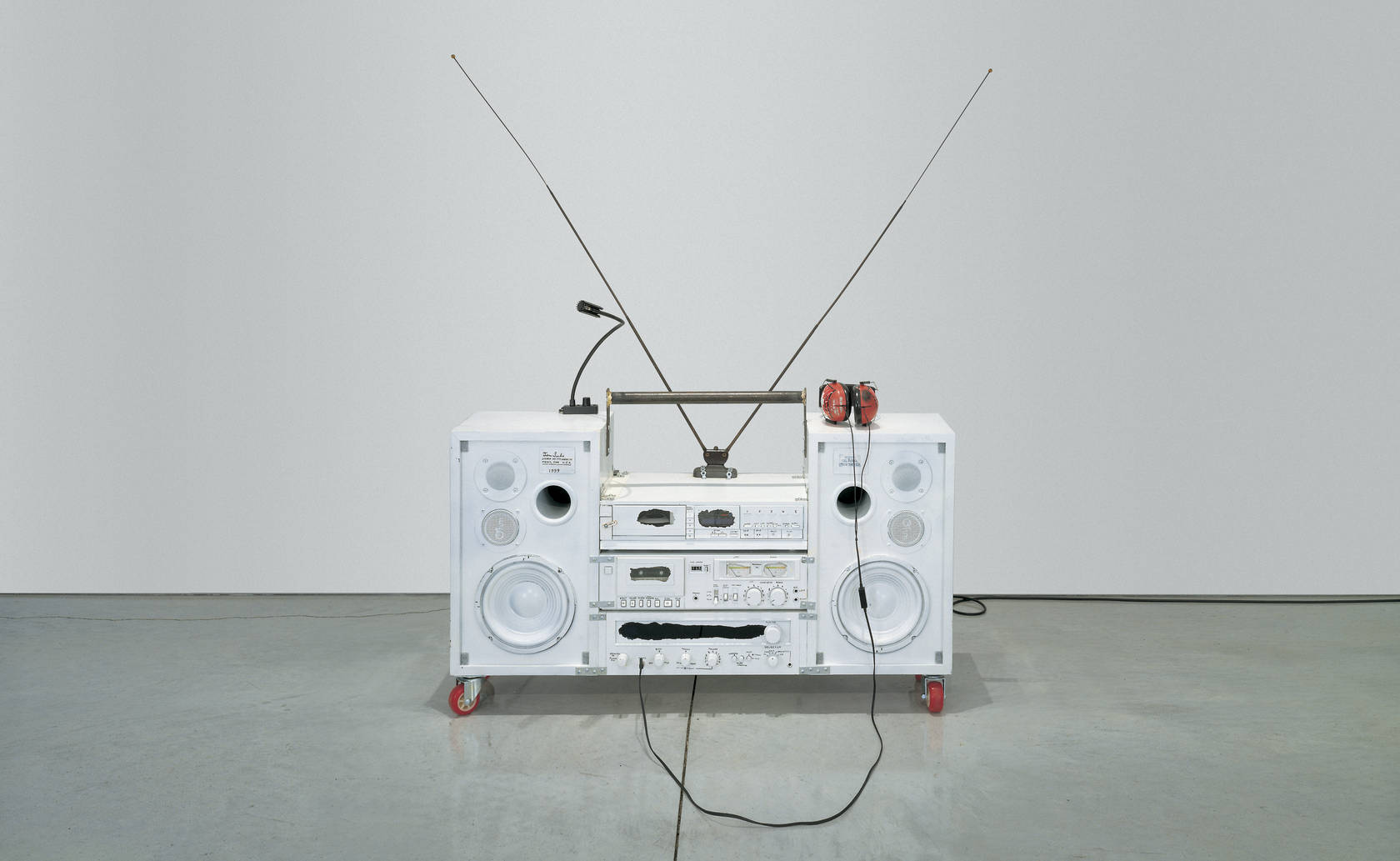

Tom Sachs, Model One, 1999. Mixed media. 32 x 41 x 14 inches. Collection of Shelley Fox Aarons and Philip Aarons, New York. Image courtesy Tom Sachs Studio.

…[T]he boomboxes strike as an uncommonly personal side project.

Tom Sachs is best known for his ersatz approximations of useful machines and

objects: bathroom fixtures fashioned from cardboard Prada boxes, faux Swiss

passports dispensed from behind a bulletproof bodega window. These clever

commodities reached a peak i n 2012 with his Creative Time-backed takeover

o f New York’s Park Avenue Armory for “Space Program: Mars,” in which the

artist mounted a participatory interplanetary installation featuring replicas of

all-terrain vehicles, a mission control room, a suit-up station, lab units for

scientific measurement, and more. But in one line of Sachs’ practice, going

back to 1999, the jerry-rigged machines actually work: his boomboxes, 22 of

which just went on view at the Brooklyn Museum.

A s Sachs recalls, “I have been making boomboxes since childhood. I hooked

my Sony Walkman up to a set of mini speakers and Velcroed them to a block of

scrap plywood. It was a clusterfuck of wires. In 8th-grade woodshop, I made a

box for the whole mess out of pine. It had a knob to hang the headphones that

was made out of a broomstick.” After stints at the London School of

Architecture and i n Frank Gehry’s studio, he continued in the same vein as a

young sculptor in New York, creating bricolage versions of things he wanted

to possess, like Mondrians outlined in gaffer’s tape on plywood. According to

the show’s curator, Eugenie Tsai, “One of the most distinctive aspects of

Sachs’s sculptural practice is his transformation of ordinary materials into

playful and scrappy one-of-a kind objects. What is amazingly consistent in

the works from 1999 to the present is the degree of invention and the evidence

of the [artist’s] hand in each object, no matter how large or small.”

Each boombox has a distinct personality. The earliest piece in the show, Model

One, from 1999, is the most humble in stark, hand-painted white, but they

quickly grew more fanciful, as demonstrated by the umbrella-topped Guru’s

Yardstyle from the same year. More recent iterations like Phonkey, 2011, and

Sarah, 2014, incorporate inventive appendages from his larger space series

and recent focus on Japan. Part creative recycling of obsolete technology, part

salute to their use as a protest tool, part fanboy homage to the music they

blasted (disco, early hip-hop) in their heyday, the boomboxes strike as an

uncommonly personal side project. Sachs told T Magazine during the

installation of the show’s previous iteration, at the Contemporary Austin,

“The nostalgia I feel for these boomboxes is intense. But it’s not exactly

nostalgia-because I haven’t let them go.”

For those who crave the surround Sachs experience, check out the artist’s

fully-fledged homage to the Japanese tea ceremony at the Noguchi Museum in

Queens, through July 24, and mark your calendars for June 16, when Sachs

and Questlove will host a discussion about art, science, and music.